Federal park employees were unemployed for five weeks. Now it’s back to business as usual. Olek Chmura doesn’t buy it.

March 30 2025

On the morning of March 20th, I met OIek Chmura outside the Visitor’s Center in Yosemite Valley. The valley was brown and damp, on the cusp of a spring bloom that I would miss by a few days. Chmura was cheery, and for good reason. He’d just found out he’d been reinstated as a park janitor after being fired just five weeks before.

Leading up to DOGE’s federal employment purge, Chmura usually spent 10 hours a day cleaning toilets, removing trash from roads and hiking trails, and emptying the many garbage cans across the 748,542 acres of Yosemite National Park. By early February, he had heard about DOGE threats to slash positions like his, and sure enough, on February 14, Chmura, along with thousands of other federal employees, received an email announcing he was terminated on account of poor performance.

“My boss and I both knew it was bullshit, because I got performance reviews in the past saying that I went above and beyond expectations,” Chmura said.

Still, his reinstatement came as a pleasant surprise. As Chmura and I strolled through El Cap Meadow, he was ecstatic. “Lunch on me!” he insisted.

Chmura suspects that the mass firings on February 14, which many federal employees have come to grimly refer to as the “Valentine’s Day Massacre,” largely served the purpose of “traumatizing” the workforce and coercing long-standing employees into “retirement.”

And this suspicion is not unfounded; in 2023, Russel Vought, the current director of the United States Office of Management and Budget, told the Center for Renewing America “We want the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected. When they wake up in the morning, we want them to not want to go to work.”

“To have that guy as your boss is kind of a pain in the ass,” Chmura told me.

Chmura lives 20 minutes outside of Yosemite Valley in El Portal, a little hamlet occupied mainly by park employees. He filled his five weeks of unemployment with a lot of reading, including Edvard Radzinsky’s biography of Stalin and Fidel Castro’s autobiography. “Dictator’s stories have always been interesting to me,” Chmura told me.

He had also fallen in love with baking, which he described through a dreamy grin: “I made an apple pie the other day and I had it sitting out on the window sill. I’ve always wanted to do that.”

Mostly, however, when the weather permitted, Chmura went climbing.

Climbing had been Chmura’s original impetus for moving to Yosemite in 2020. He spent his first year in the valley dirtbagging — sleeping in his ailing Ford Ranger, charming the food court employees into giving him fries, exchanging beers with his fellow valley-dwellers, all to maximize his time spent scaling the granitic domes that define Yosemite Valley as the global climbing mecca.

For Chmura, it was the climbing access that justified leaving his well-paying plumbing job in Cleveland, Ohio and moving to the valley, and it was the climbing access that justified his staying there, even after his termination.

“I don’t have too much to lose, I’m just a dude with a cute girlfriend. But I know guys that have kids and mortgages. I worry about them,” he told me.

Part of Trump’s federal Reduction in Force includes payroll cuts of 10-30% for Yosemite National Park employees, according to Chmura. “They’re trying to make it so miserable that federal workers will quit,” he said.

Yosemite, along with most other national parks, is already operating on a barebones budget, according to the Sierra Sun Times. Even before Trump took office, the park was understaffed. Chmura’s theory is that once enough park workers resign, forcibly or otherwise, there will be ample evidence that the national parks are failing to operate under the care of federal workers and, as a result, they must be privatized.

“It’s very low morale right now,” Chmura said.

In response to the emotional burnout, early into his unemployment, Chmura started a movement to unionize his federal coworkers. A union, Chmura hoped, would help defend against Yosemite’s privatization as it would equip him and other park employees with legal protection.

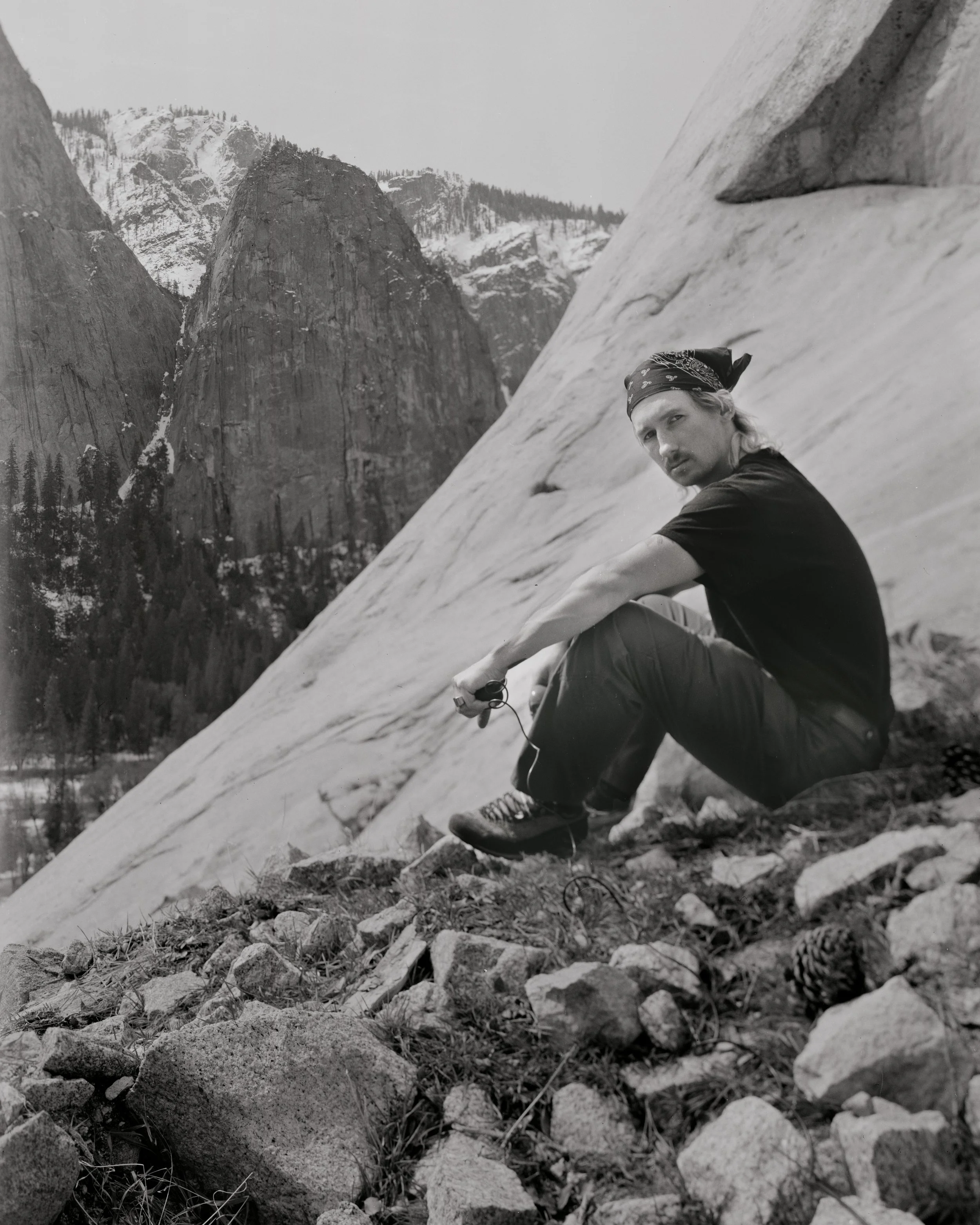

In order to gain representation, half of the park’s employees needed to sign up for the union. So, using a dented whiteboard and a blue dry erase marker, Chmura made a “FEDS UNIONIZE HERE!” sign and started posting up outside the community hall in El Portal.

The Caroll N. Clark Community Hall is a squat, tan brick building at the center of town. When I arrived there to meet Chmura for an evening of unionizing, it was bustling. A bluegrass band was playing Watchouse covers and the small kitchen had been converted into a pop-up taqueria. People were carrying loaded plates of carne asada and veggies to the back lawn where the Yosemite Employee Association (YEA) had set up a makeshift bar. Chmura stood at a picnic table, wearing a flannel and his signature black bandana, holding in one hand his conspicuous whiteboard sign and in the other, the union sign-up sheet. He was only 20 signatures short of the union requirement.

While I worked on my own plate of tacos, I watched as dozens of people approached Chmura to chat or to give him a hug, congratulating him on his reinstatement. He enthusiastically delivered his union spiel and handed his clipboard to anyone who would take it, emphasizing the importance of unionizing in light of the federal government’s wishy-washy backtracking.

“It's been really awesome to see the way the community came together,” Olek told me. Then added, “I’m probably still gonna get fired!”

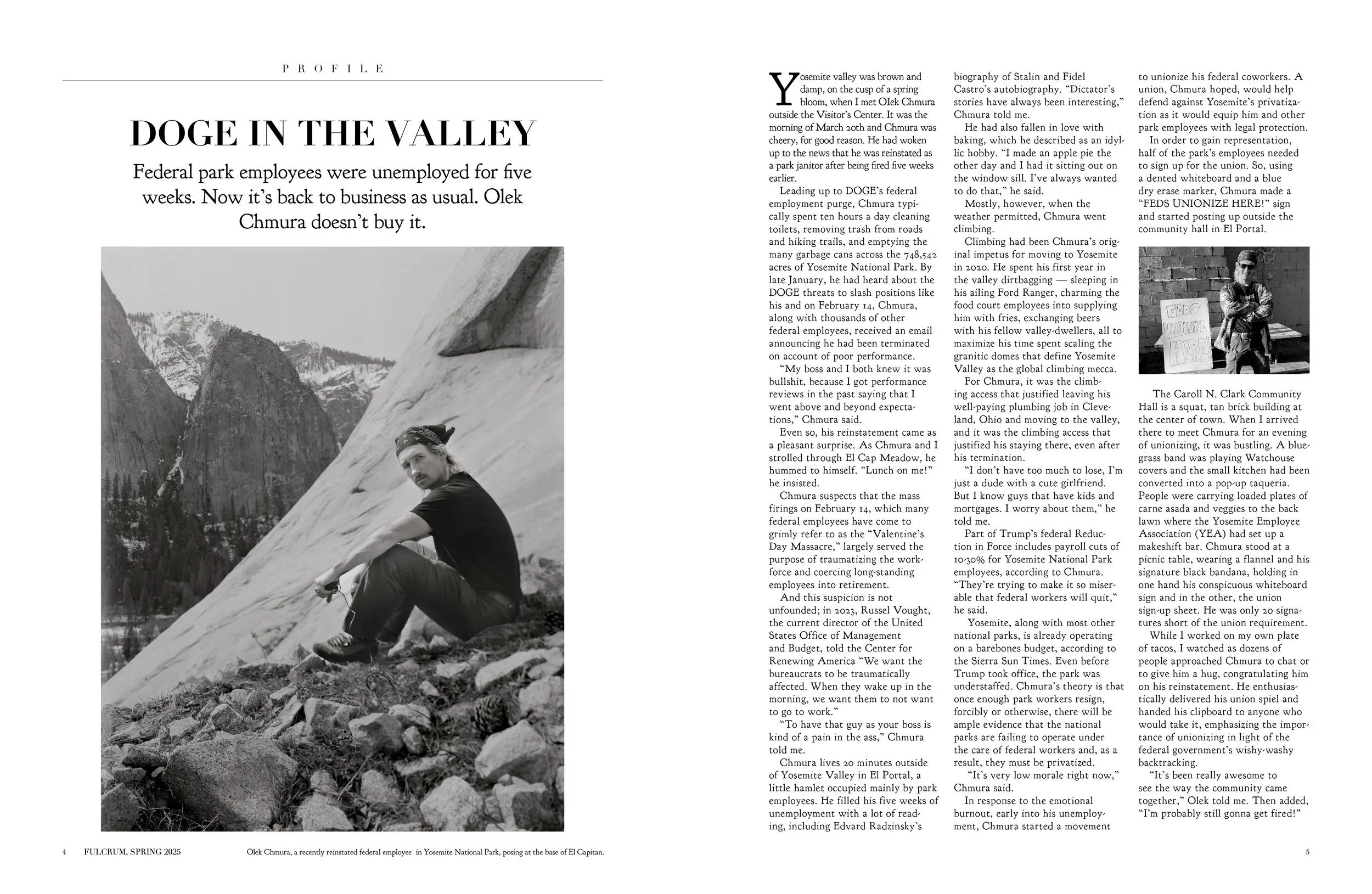

Olek Chmura, a recently reinstated federal employee in Yosemite National Park, posing at the base of El Capitan.